Two Fantastic Planets

Fantastic Planet, the movie

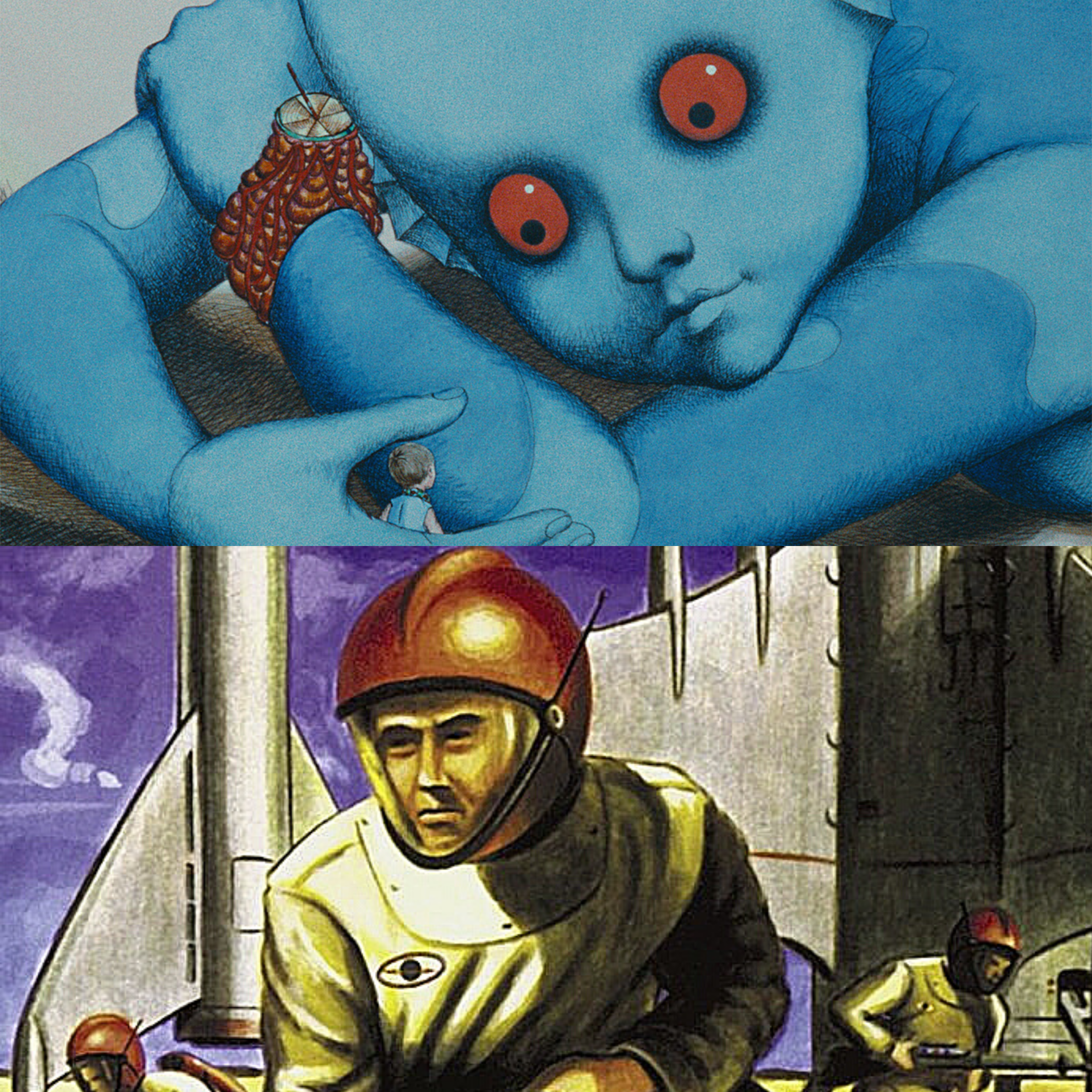

There are two prevailing theories on what the central theme of Fantastic Planet (orig. La Planète sauvage, lit. The Wild Planet), the classic 1973 French animated film directed by René Laloux, is: animal rights or racism. There is no doubt, however, that the movie centers on one key message, irrespective of how you choose to interpret it's theme: it's wrong for the powerful to use their might to oppress the powerless. In many ways, it’s a parable: in the distant future, the planet Ygam is populated by the Draag, a large, blue humanoid species of a higher-than-human intelligence and a longer-than-human lifespan, the Om (the Draag name for humans), who the Draags often domesticate, but, if found in the wild, exterminate, and a variety of strange plants and animals. The story centers on Terr, a domestic Om, who, through a kink in his electronic leash is able to receive lessons intended for his Draag owner, Tiwa, who uses this information to liberate the colonies of wild Oms on Ygam. It’s a simple story told beautifully, particularly thanks to Roland Topor, whose surreal illustrations render the imagined world incomparable to anything else in the visual medium, even today, nearly five decades on.

Fantastic Planet, the album

I came to this movie as a trve kvlt hipster in college, after having heard the album of the same name by 90s alt-rejects Failure. Running the same sixty-eight minutes as the movie, Fantastic Planet is an incomparable mish-mash of 90s alternative rock, prog, and space rock. Its themes are far more personal: addiction, recovery, alienation, delusion. Starting with two straight-out alt-metal bangers, Saturday Saviour and Sergeant Politeness, the album bobs and weaves through proggy instrumental tracks (like Segues 1, 2, and 3), soft-then-loud non-grunge alt (like Dirty Blue Balloons), dissonant rock (like the Nurse Who Loved Me, covered by A Perfect Circle, a band that included ex-Failure guitarist, Troy Van Leeuwen, on Thirteenth Step), and space rock (like Another Space Song). Throughout, there isn’t a single moribund chord progression or throwaway lyric. The band draws some inspiration from both the film’s soundtrack, a sequence of Pink-Floyd-meets-jazz-fusion tracks by Alain Goraguer, and its visuals, as evidenced in the cover art, likely a reimagining of the escape from Ygam that Terr initiates.

Irreconcilable similarities

To me, these two works of art will likely always be linked. While there’s no doubt that the album draws inspiration from the film, it’s nowhere near relevant to the album’s themes, its noisy alt sound, or really even its ‘feel’. The film, like most parables, ends on a note of reconciliation, a stable equilibrium. The album is as off-kilter as ever in its final minutes – Heliotropic in particular is a dissonant arena-emptier. However, even today, when I listen to the album, I think of the movie (and vice-versa). And once I’m done with either the album or the movie, I think the same thing I thought over a decade ago: the only two things these two things have in common is their identical names and their comparable runtimes. But my mind can’t separate the two. In fact, my previous viewing of Fantastic Planet the movie was with Fantastic Planet the album as soundtrack, and I loved it. I can’t say it was a significantly better experience than the intended experience of the album or the movie, but I can say it was sufficiently different to warrant recommending. We Oms are curious creatures.

Just purely as an experiment on societal norms, at what point would the average human bean find not crying in the cinema weirder than crying in one. How deep must the tragedy pictured be, how profound the sense of loss, how unbearable the pain of two dee characters, before your average dudebro thinks not crying would be perceived as a sign of serious apathy, psychopathy / sociopathy even.